Why Blaming Tech for Kids’ Cognitive Decline Misses the Real Problem

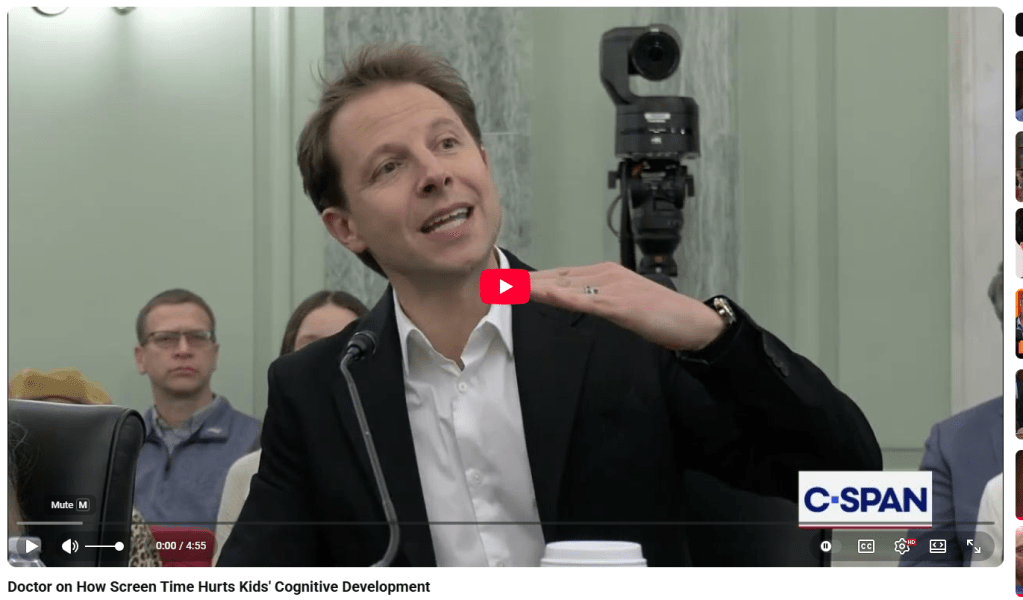

You’ve probably seen that video from the recent Senate hearing where Dr. Jared Cooney Horvath talks about how tech like screens and digital tools in schools is causing big drops in kids’ brain skills. He points to shorter attention spans, weaker memory, lower reading and math levels, and even falling IQ scores among young people today. He says Gen Z is the first group to do worse than their parents on these tests, even with more years in school. And he blames it all on too much tech starting early in education.

But hold on. While his points sound scary, he’s pointing the finger at the wrong thing. Tech isn’t the main villain here. The real issue is how school lessons – what we call the curriculum – have changed over the last few decades. They’ve become less tough and more focused on making everyone feel included, which often means lowering the bar for what kids need to learn. This “dumbing down” is what’s really hurting kids’ thinking skills, like planning, remembering, and solving problems. Let’s break this down step by step, with facts, so you can see for yourself.

First, What Did Schools Teach in the 1980s Compared to Now?

Back in the 1980s, school was harder in many ways. Lessons focused on building strong basics like reading, writing, math facts, and history facts. Kids had to memorize things, practice a lot, and face tough tests without much hand-holding. For example, in math, there was a big push on learning to add, subtract, multiply, and divide by hand – no calculators for the easy stuff.

Science and history classes drilled key facts and skills, such as naming states and understanding timelines. Kindergarten was mostly play-based, with simple ABCs and numbers, not full-on reading or math like today.

Fast forward to the 2020s, and things look different. Starting in the late 1980s and ramping up in the 1990s, states began setting “standards” – rules for what kids should know each year. This sounded good, but it led to big shifts. To make schools more “fair” and “inclusive,” many places cut back on hard challenges. They got rid of advanced classes for gifted kids, stopped tracking students by skill level, and focused more on group work and feelings over facts. Math now stresses “problem-solving” over basic calculations, but without strong basics, kids struggle.

Reading programs switched from phonics (sounding out words) to “whole language” (guessing from pictures), which hurt literacy. And with tests like those from No Child Left Behind in the 2000s, teachers narrowed lessons to just math and reading, skipping art, history, and science to boost scores. hoover.org +3The result? Standards have dropped. Today, many high school grads can’t name all 50 states or do simple math without help. National tests show only about 25% of kids are good at reading or math, and literacy rates are falling – 28% of adults now read at the lowest level, up from 19% a few years ago.

From the previous conversation’s sources. This isn’t because of tech; it’s because lessons cater to the “lowest common denominator” to include everyone, but that means less challenge for building strong brains.

Rebutting the Doctor: Tech Isn’t the Culprit – It’s a Tool for GoodDr. Horvath says tech like tablets in class hurts attention and memory because kids multitask too much. But studies show the opposite: when used right, tech boosts skills. For example, surgeons who play video games do better in real operations. A big study of 33 doctors found that those who gamed more than three hours a week made 37% fewer mistakes, finished tasks 27% faster, and scored 42% higher overall in laparoscopic surgery – that’s keyhole surgery needing fine hand-eye skills. Games train quick thinking and precise moves, which transfer to real life.

He’s deflecting blame from the real fix: making curricula tougher again. Blaming screens lets us ignore how we’ve softened education to avoid “inequity.” But equity shouldn’t mean lowering standards – it should mean helping everyone reach higher ones.

How Tech Actually Helps Brains Grow Stronger

Some people see tech as a “crutch” that makes us lazy. But really, it’s leverage – it handles boring, repetitive tasks so we can tackle harder stuff. Think about the calculator: In the old days, kids spent hours on long division. Now, calculators do that fast, freeing brains for big ideas like algebra or real-world problems. Studies show calculators build curiosity and deeper math understanding, letting kids test ideas quickly and focus on why numbers work, not just crunching them.

Spreadsheets take it further. They organize data, run formulas, and make graphs in seconds. This lets students dive into complex analysis without getting stuck on the basics. For instance, in science class, kids can model weather patterns or budgets without manual charts. Research shows spreadsheets boost critical thinking and quantitative skills, helping with open-ended problems and even STEM careers. Instead of wasting brain power on simple adding, people solve tougher puzzles, like engineers designing bridges or economists predicting trends.

History proves this: When typewriters came out, some said they’d ruin handwriting. But they let writers focus on ideas, not perfect letters. Tech isn’t a crutch; it’s a ladder to higher learning for those who use it smartly.The Bottom Line:

Barking Up the Wrong Tree

Dr. Horvath and others are factually wrong to pin cognitive decline all on tech. The data shows curriculum changes – from rigorous basics in the 1980s to today’s watered-down, inclusive-but-less-challenging lessons – are the bigger cause. We’ve lowered expectations to make things “fair,” but that’s left kids with weaker executive functions and knowledge gaps. Tech, when done right, actually sharpens skills and frees minds for complex work.

If we want smarter kids, fix the curriculum: Bring back challenge, basics, and high standards for all. Don’t demonize tools that can help.

Leave a comment