Picture this: I’m at a local Halton Region event, trying to avoid surfing on my iPhone when the organizer steps up to the mic. Before diving into the agenda, she solemnly intones, “We acknowledge that we are on the traditional territory of the Anishinaabe, specifically the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation.” The room nods along, heads bowed in performative reverence, as if we’ve all just confessed to stealing the land ourselves. I nearly dropped my phone, not because I dispute the sentiment, but because the statement is so drenched in historical amnesia it could double as a script for a woke sitcom. Why the Anishinaabe? Why not the tribes they displaced in bloody wars long before Europeans even dreamed of docking at Halifax? And why are we pretending this land’s history began with one group’s claim, as if time itself started when the Mississaugas set up camp?

Let’s get real. The ritual of land acknowledgments has become a cultural tic, a box to check for the morally superior who think saying the right words absolves them of history’s complexities. It’s virtue-signalling dressed up as respect, and it’s time we stopped pretending it’s anything more than a feel-good gesture that ignores the messy, violent truth of North America’s pre-colonial past. The Anishinaabe, like every other Indigenous group, were not serene stewards of a static Eden. They were players in a brutal game of survival, conquest, and displacement that spanned centuries. So, let’s take a hard look at Halton Region’s history, peel back the layers of who took what from whom, and ask: why are we sanctifying one tribe’s claim when the land’s story is a saga of endless upheaval?

The Anishinaabe Didn’t Start Here: A Pre-Colonial History Lesson

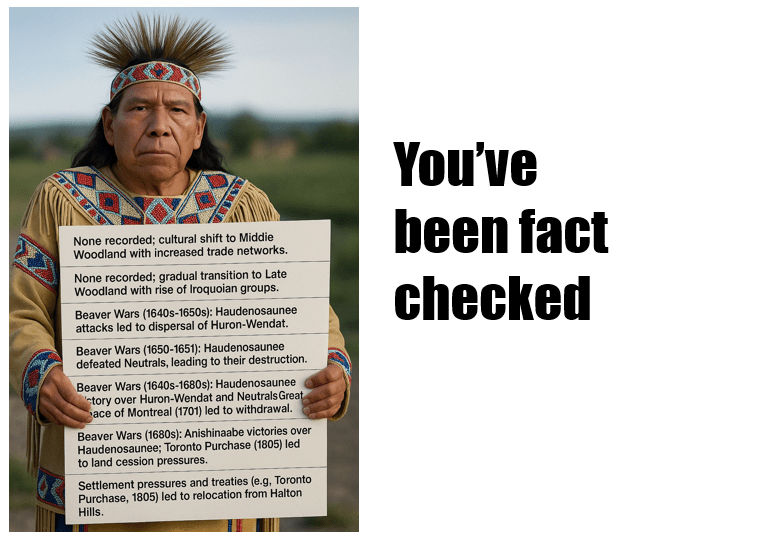

The Halton Region, nestled along Lake Ontario’s north shore, wasn’t always Anishinaabe territory. The Mississaugas, an Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) group, arrived in the area by the late 17th century, but they weren’t the first to call it home. Before them, the region was occupied by Iroquoian-speaking peoples, notably the Huron-Wendat and the Neutral Nation (Attawandaron), with the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) also exerting influence. These groups didn’t just share the land in a kumbaya circle; they fought, displaced, and sometimes obliterated each other in wars that make Game of Thrones look like a neighbourhood squabble.

Let’s rewind to the early 17th century. The Huron-Wendat, a confederacy of Iroquoian tribes, were major players in southern Ontario, including Halton. They were skilled farmers, growing corn, beans, and squash, and their villages dotted the fertile lands around the Great Lakes. But they weren’t alone. The Neutral Nation, another Iroquoian group, occupied areas west of Halton, including parts of what’s now Hamilton and Niagara. These groups traded, allied, and occasionally clashed, but their dominance was upended by the Beaver Wars (1640s–1680s), a series of conflicts driven by competition for fur trade dominance and European firearms.

Enter the Haudenosaunee, the Iroquois Confederacy (comprising the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and later Tuscarora). Armed with Dutch muskets, the Haudenosaunee launched a campaign of conquest to control the fur trade. By the 1640s, they targeted the Huron-Wendat, whose alliance with the French made them both rivals and targets. The Haudenosaunee attacked Huron villages with ruthless efficiency, destroying settlements and dispersing survivors. By 1649, the Huron-Wendat were nearly annihilated, their population decimated by warfare and European diseases like smallpox, to which they had no immunity. Survivors fled north or were absorbed into Haudenosaunee communities.

The Neutral Nation didn’t fare much better. In 1650–1651, the Haudenosaunee turned their sights on the Neutrals, who had tried to stay out of the Huron conflict. The Neutrals’ territory, rich in beaver-hunting grounds, was too tempting. By 1651, the Haudenosaunee had overrun Neutral villages, killing or assimilating thousands. The Neutral Nation effectively ceased to exist, their lands left vacant or occupied by Haudenosaunee hunters. Halton, part of this contested zone, became a Haudenosaunee sphere of influence, though they didn’t establish permanent settlements there.

So, where were the Anishinaabe during this carnage? The Mississaugas, part of the broader Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) nation, were further north, around the upper Great Lakes. But the collapse of the Huron-Wendat and Neutral nations created a power vacuum in southern Ontario. By the late 17th century, the Mississaugas moved south, capitalizing on the Haudenosaunee’s eventual withdrawal after peace negotiations with the French in the 1701 Great Peace of Montreal. The Mississaugas didn’t politely ask for permission to settle Halton; they took it, establishing seasonal villages along the Credit River and Lake Ontario’s shores. Their arrival wasn’t a peaceful migration—it was a strategic occupation of lands left open by earlier wars.

The Beaver Wars: Not Exactly a Love Story

The Beaver Wars, often mischaracterized as a simple trade dispute, were a masterclass in pre-colonial geopolitics. Triggered by the depletion of beaver populations in Haudenosaunee territory, the wars were about controlling the fur trade routes that Europeans, especially the French and Dutch, were turning into goldmines. The Haudenosaunee, backed by Dutch firearms, sought to dominate the trade by eliminating middlemen like the Huron-Wendat and Neutral Nation, who supplied furs to the French. The Anishinaabe, including the Mississaugas’ ancestors, weren’t innocent bystanders. Allied with the French, they fought the Haudenosaunee in skirmishes across southern Ontario, eventually pushing them back south of Lake Ontario by the 1680s. These victories allowed the Mississaugas to expand into Halton and beyond.

Let’s not romanticize this. The Anishinaabe’s southward push wasn’t a noble reclamation of ancestral lands; it was a calculated move to seize territory from weakened rivals. The Mississaugas built seasonal villages in Halton, fishing, hunting, and trading furs, but their claim was no more “original” than that of the Huron-Wendat or Neutrals before them. And before the Iroquoian groups? Archaeological evidence suggests Palaeoindian and Archaic peoples, likely Algonquian-speaking ancestors, roamed the area as early as 11,000 years ago, hunting megafauna and gathering wild plants. Their descendants may have been pushed out or absorbed by later Iroquoian arrivals. The point? Halton’s land has changed hands more times than a poker chip in a casino.

Why the Anishinaabe? The Virtue-Signalling Conundrum

So why do we single out the Anishinaabe in land acknowledgments, as if they’re the eternal victims of history’s roulette? It’s not because they were the first or only occupants of Halton. It’s because they were the last Indigenous group standing when Europeans arrived, making them the ones who signed treaties, like the Toronto Purchase (Treaty 13, 1805)—and bore the brunt of colonial dispossession. The Mississaugas ceded millions of acres, including Halton, to the British for pennies, often under dubious circumstances. Their losses were real, their grievances legitimate. But elevating them as the sole “rightful” owners erases the Huron-Wendat, Neutrals, and others who were displaced in equally brutal ways, just without a European audience to document it.

This selective memory is where the virtue-signalling kicks in. Land acknowledgments often feel like a shortcut to moral absolution, a way to say, “We’re sorry for colonialism,” without grappling with the fact that pre-colonial history was no utopia. The Anishinaabe weren’t saints; they were survivors in a world where survival meant fighting, conquering, and sometimes displacing others. The Huron-Wendat and Neutrals could tell you stories of “land theft” at Haudenosaunee hands, just as the Mississaugas could point to British treaties. So why stop at the Anishinaabe? Why not acknowledge the Neutrals, whose villages were burned to ash? Or the Huron-Wendat, scattered to the winds? Or the nameless Archaic hunters who roamed Halton millennia ago? The answer: it’s easier to pick one name, one story, and call it a day.

This isn’t to diminish the Anishinaabe’s losses or their cultural significance. The Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation continue to assert their rights and heritage, and their story matters. But pretending they’re the alpha and omega of Halton’s Indigenous history is intellectually lazy. It’s like starting a book at chapter 10 and claiming you know the whole plot. And when we parrot these acknowledgments without questioning them, we’re not honoring history—we’re sanitizing it.

The Real History: Atrocities Aren’t Exclusive to Europeans

Let’s talk atrocities, because the narrative of pre-colonial harmony is a myth that needs debunking. The Beaver Wars weren’t just about trade routes; they involved massacres, village burnings, and prisoner torture. The Haudenosaunee didn’t just “displace” the Huron-Wendat—they killed thousands, sometimes ritualistically, to demoralize their enemies. Captives were often tortured, mutilated, or adopted to replace lost warriors. The Neutrals faced similar fates, their population collapsing under Haudenosaunee assaults. And the Anishinaabe? Their alliances with the French included raids on Haudenosaunee villages, with plenty of bloodshed to go around.

These weren’t anomalies. Intertribal warfare was common across North America, driven by resource competition, revenge, or prestige. The Jesuit Relations (1632–1673), accounts by French missionaries, describe Indigenous groups in southern Ontario engaging in practices like cannibalism, enslavement, and scalp-taking—hardly the peaceful coexistence of popular imagination. The Haudenosaunee’s near-genocide of the Huron-Wendat in 1649 wasn’t an outlier; it was a high-stakes move in a world where power meant survival.

Europeans didn’t introduce violence to North America; they amplified it with guns, diseases, and colonial ambition. But pretending Indigenous peoples were passive victims before 1492 is as dishonest as pretending colonialism was a polite land deal. The Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, Huron-Wendat, and Neutrals were all actors in a complex, often brutal drama. Singling out one group for homage ignores the others who fought, bled, and died for the same soil.

Where Do We Draw the Line?

Here’s the rub: history doesn’t have a neat starting point. If we acknowledge the Anishinaabe because they held Halton when Europeans arrived, why not the Huron-Wendat, who farmed it before the Beaver Wars? Or the Neutrals, whose hunting grounds spanned the region? Or the Archaic peoples, whose spearpoints litter Halton’s archaeological sites? If we’re going back to “time immemorial,” as some acknowledgments claim, why stop at humans? Why not thank the mastodons who grazed here 12,000 years ago? It’s absurd, but it exposes the arbitrary line-drawing of these rituals.

The truth is, land acknowledgments often reflect political expediency, not historical rigor. The Anishinaabe are recognized because their descendants, like the Mississaugas of the Credit, are still here, advocating for their rights. The Huron-Wendat and Neutrals don’t have the same visibility, their communities scattered or absorbed. But that doesn’t make their claim to Halton less valid—it just makes it less convenient for the narrative.

So, what’s the alternative? If we’re serious about respecting history, let’s ditch the rote acknowledgments and have real conversations. Teach the Beaver Wars in schools, not as a footnote but as a saga of power and survival. Highlight the Huron-Wendat’s agricultural prowess, the Neutral Nation’s trade networks, the Haudenosaunee’s military genius, and the Anishinaabe’s strategic resilience. Acknowledge the treaties that screwed over the Mississaugas, but don’t pretend their story is the only one. And for God’s sake, stop acting like saying the right words at a podium undoes centuries of conflict.

A Call to Think, Not Signal

I get it—land acknowledgments feel like a step toward reconciliation. But they’re a shallow one, especially when they gloss over the fact that Halton’s history is a palimpsest of conquests, not a single theft. The Anishinaabe deserve respect, but so do the Huron-Wendat, the Neutrals, and the countless others whose bones lie beneath our suburbs. If we’re going to talk about land, let’s talk about all of it—the wars, the betrayals, the resilience, the whole bloody mess.

Next time you’re at an event and someone starts droning about the Anishinaabe’s “traditional territory,” don’t just nod along. Ask: “What about the Huron-Wendat? The Neutrals? Who came before them?” Watch the room squirm. Better yet, crack open a book—try The Canadian Encyclopedia or The Jesuit Relations, and learn the real story.

History isn’t a bumper sticker; it’s a battlefield. And if we honour it, let’s do it with facts, not feelings.

Because here’s the kicker: virtue-signalling doesn’t change the past. It just makes us dumber about it. And in Halton, where the land has seen more owners than a used car lot, that’s a sin we can’t afford.

Leave a comment