Wildfires – What They Don’t Want You to Know

Until the recent Canadian wildfires sent plumes of smoke over the densely populated cities around the Great Lakes and Eastern Seaboard, few urban residents had ever experienced the eerie orange haze of a forest fire or the sudden spike in fine particulates and pervasive smell of smoke. Unsurprisingly, many people reacted with alarm. We city dwellers typically encounter wildfires only through television, usually accompanied by footage of fire crews and water bombers valiantly combating the flames. This coverage fosters the perception that wildfires are unnatural events to be avoided at all costs. In reality, forest fires are not only natural but essential to the forest ecosystem’s life cycle.

Unfortunately, politicians, reporters, and climate activists quickly seized this unusual event to further their agendas. They made numerous glib claims about climate change causing wildfires to become more common. For instance, Prime Minister Trudeau tweeted, “We’re seeing more and more of these fires because of climate change.”

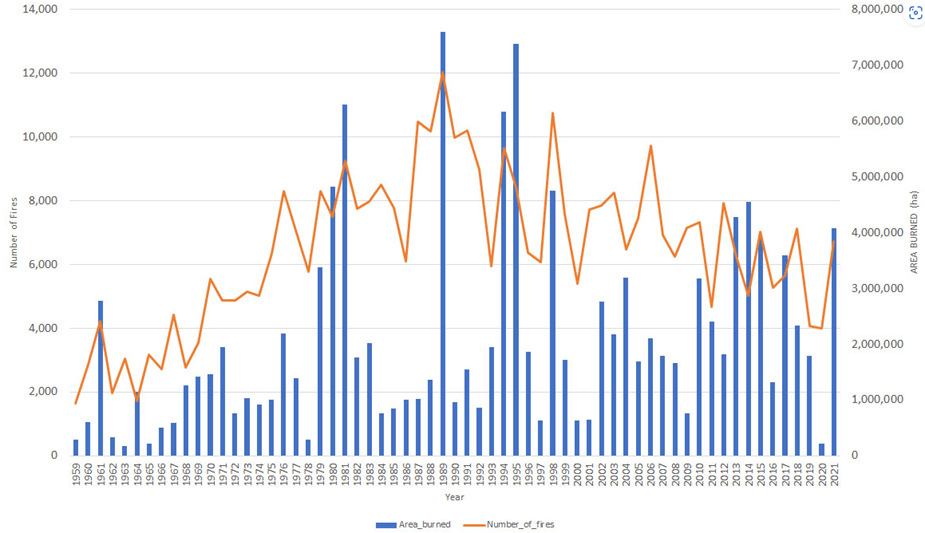

This statement is false. Amid the smokescreen of untrue claims, no one seemed to check the actual numbers. Canadian forest fire data are available from the Wildland Fire Information System. Wildfires have been getting less frequent in Canada over the past 30 years (see chart below). The annual number of fires increased from 1959 to 1990, peaking in 1989 at just over 12,000, and has been trending down since. From 2017 to 2021 (the most recent interval available), there were about 5,500 fires per year, half the average from 1987 to 1991.

The annual area burned by wildfires also peaked 30 years ago. It increased from 1959 to 1990, hitting a high of 7.6 million hectares in 1989, then dropped to an average of 2.4 million hectares per year from 2017 to 2021. In 2020, we saw the lowest point on record, with just 760,000 hectares burned.

Data shows the proportion of fires each year that become major (over 200 hectares in size) peaked in 1964 at 12.3 percent. From 1959 to 1964, it averaged 8.7 percent, then fell to 3.4 percent in the early 1980s. As of the 2017 to 2021 interval, it had climbed again to 6.0 percent, still well below the average from 60 years ago (see chart below).

Satellite data from the European Space Agency reveals that global wildfire activity has been trending downward in recent decades and is now nearing its lowest level since records began in the early 1980s.

In a detailed discussion on the Royal Society blog in 2020, U.K. forestry experts Stefan Doerr and Cristina Santin acknowledged that climate change might make conditions for fire more favorable in some areas while reducing them in others. The tendency for some fires to become larger and more dangerous can be traced back to our forest management practices. They explained, “[Very] aggressive fire suppression policies over much of the 20th century have removed fire from ecosystems where it has been a fundamental part of the landscape rejuvenation cycle.” This has led to a build-up of fuel in the form of woody debris, increasing the risk of more explosive and unstoppable fires.

“We cannot completely remove fire from the landscape,” they stressed. “That misconception led to the ‘100% fire suppression’ policies in the US and elsewhere that have worsened many situations.”

As Environmental Studies professor Roger Pielke Jr. notes on his Substack, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is also hesitant to link forest fire activity directly to climate change. While it acknowledges an increase in “fire weather” (hot, dry conditions conducive to forest fires) in some regions globally, it does not claim a “signal” of greenhouse gas influence on the probability of fire weather, nor do they expect one to be detected in the coming century.

When it comes to climate change, we’re constantly told to “follow the science.” Yet, the same people who champion this often fabricate claims about trends in forest fires both in Canada and globally, linking them to climate change. Science tells us forest fires are not becoming more common, and the average area burned peaked 30 years ago. It also tells us greenhouse gases won’t put out fires, and raising the carbon tax will only make it more expensive to fight the fires currently burning.

Leave a comment