I reported this over 36 months ago and was called a conspiracy theorist.

Nearly three years ago, I delved into the complex world of pharmaceutical efficacy and marketing in an article that sparked considerable debate. At the time, my observations and conclusions were met with skepticism, with some even labelling my assertions as conspiratorial. However, as more data and information have come to light, the landscape is beginning to shift, and the once-dismissed notions are now being viewed in a new light.

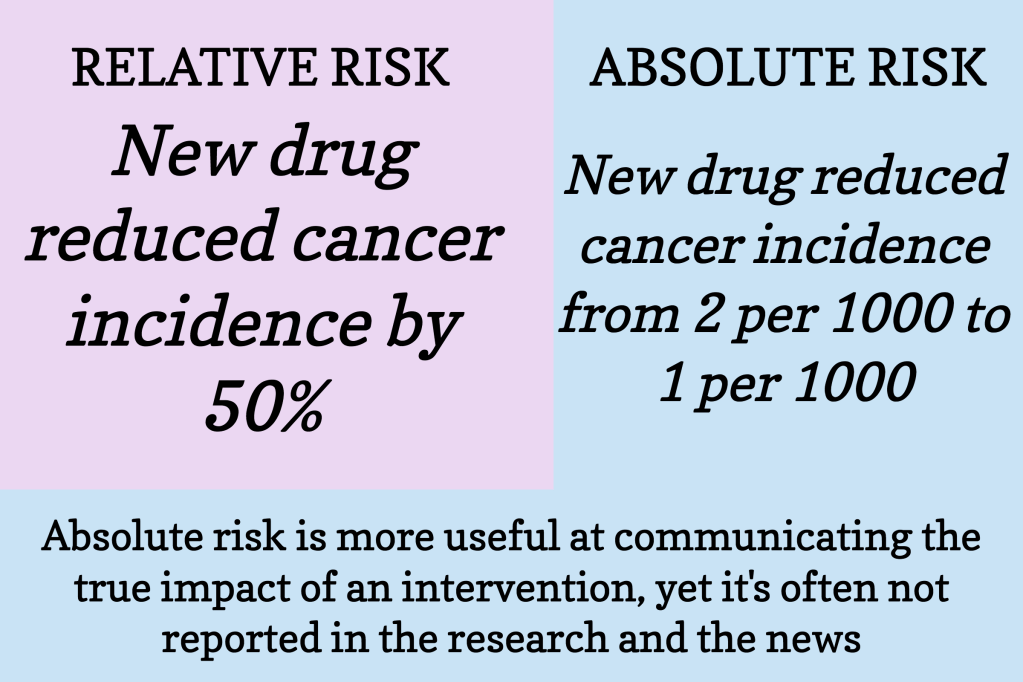

In my previous work, I emphasized the critical need for transparency and accuracy in how pharmaceutical companies report the efficacy of their products, particularly in the context of vaccines and life-saving drugs. I pointed out the potentially misleading nature of presenting drug efficacy predominantly in relative terms rather than absolute figures—a practice that can dramatically skew public perception and decision-making.

As time has passed, the revelations and findings about the pharmaceutical industry have increasingly aligned with the concerns I raised. Reports and lawsuits, such as the recent case against Pfizer by the Texas Attorney General, have begun to unravel the complexities and potential misrepresentations in the reporting of vaccine efficacy. These developments not only validate the concerns raised in my earlier article but also underscore the importance of ongoing scrutiny and analysis in this vital field.

The unfolding narrative around pharmaceutical practices serves as a reminder of the importance of critical inquiry and evidence-based analysis. It is a testament to the power of persistent research and the pursuit of truth, especially in areas as impactful as public health and safety. As we continue to navigate these complex issues, the insights from past research become ever more relevant, shaping our understanding and guiding our path forward.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has filed a lawsuit against Pfizer, alleging that the company misled the public regarding the efficacy of its COVID-19 vaccine. The lawsuit claims that Pfizer’s representation of its vaccine as having 95% efficacy was misleading because this figure represented a “relative risk reduction” as observed in the initial two-month clinical trial results. Paxton argues that this is a deceptive metric and that the vaccine’s “absolute risk reduction” showed it to be only 0.85% effective.

The lawsuit also accuses Pfizer of misrepresenting the durability and the extent of protection offered by its vaccine, particularly in the context of transmission and long-term effectiveness. Paxton alleges that Pfizer engaged in false, deceptive, and misleading acts by making unsupported claims about the vaccine’s efficacy in violation of the Texas Deceptive Trade Practices Act. The complaint includes accusations that Pfizer attempted to censor public discussion and silence critics who threatened to reveal the truth about the vaccine’s efficacy. As a result of these alleged misrepresentations, the lawsuit seeks to stop Pfizer from making further alleged false claims and to impose fines exceeding $10 million for these purported violations.

Pfizer has responded to the allegations by stating that their representations about the vaccine have been “accurate and science-based.” The company asserts that its vaccine has demonstrated a favourable safety profile and has been effective in protecting against severe COVID-19 outcomes, including hospitalization and death.

This lawsuit is part of a broader scrutiny of Pfizer’s practices, as Paxton had previously initiated investigations into Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson regarding their vaccines’ efficacy claims. Additionally, this is Paxton’s second lawsuit against Pfizer in November, with another case accusing the company and a supplier of manipulating quality control tests for drugs treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children.

In medical literature, such as articles in ‘American Family Physician’, there’s a tendency to emphasize the benefits of drug treatments predominantly in relative terms. This practice, however, can be misleading. It not only influences physicians’ prescribing decisions but also impacts patients’ willingness to accept therapy. For example, in a piece on bisphosphonates for osteoporosis, the reported 50% decrease in the risk of fractures is technically accurate. Still, it overshadows the more modest absolute risk reductions – 7% for vertebral fractures, 1.1% for hip fractures, and 1.9% for wrist fractures over three years.

This discrepancy between relative and absolute risk reductions is crucial. When advising patients about drug therapies, it’s imperative to present information in a way that enables them to make truly informed decisions. For a patient considering bisphosphonate therapy, explaining that their risk of a nonvertebral fracture could reduce from 8% to 5% over three years with the medication, and discussing potential side effects and costs, offers a clearer picture than simply stating a 50% relative risk reduction. This kind of transparent communication about the benefits and limitations of drug therapies is essential for patient autonomy and informed consent.

Therefore, it is recommended that authors and physicians alike should strive to present drug benefits in absolute terms alongside relative ones. This approach not only fosters a better understanding among patients but also supports them in making decisions that align with their preferences and circumstances.

Understanding absolute and relative risks, and how they differ, is key in evaluating the effectiveness of a medical treatment, like a vaccine or a drug. Here’s an explanation in plain language:

Absolute Risk: This is the straightforward, overall chance of something happening. For instance, if 2 out of 100 people get a certain disease, the absolute risk of the disease is 2%.

Relative Risk: This is more about comparison. It shows how much a treatment changes the risk compared to a control (like a placebo). If a treatment cuts the risk of getting a disease in half, that’s a 50% relative risk reduction. It sounds impressive, but without knowing the absolute risk, it’s hard to grasp the true impact.

Why Using Only Relative Risk Can Be Misleading:

Lacks Context: Relative risk reduction doesn’t tell you the original risk. A 50% reduction sounds great, but if it’s a reduction from 2% to 1%, the actual benefit is small.

Overstates Benefits: It can make a treatment look more effective than it really is. A big percentage decrease (relative risk) from a small original risk (absolute risk) might not be as beneficial as it seems.

Decision-making: When making health decisions, knowing the actual, tangible risk (absolute) is often more helpful than just knowing how much risk is reduced proportionally (relative).

For example, let’s say a new drug reduces the risk of a certain disease from 4% to 2%. The absolute risk reduction is 2% (from 4% to 2%). However, the relative risk reduction is 50% (because 2% is half of 4%). While saying “this drug reduces your risk by 50%” sounds impressive, the actual change in risk is just 2%.

In conclusion, while relative risk gives a sense of how much treatment can change the risk in comparison to a baseline, absolute risk provides the actual chance of an event happening. Both are important, but relying solely on relative risk without considering absolute risk can be misleading and overemphasize the effectiveness of a treatment.

Leave a comment